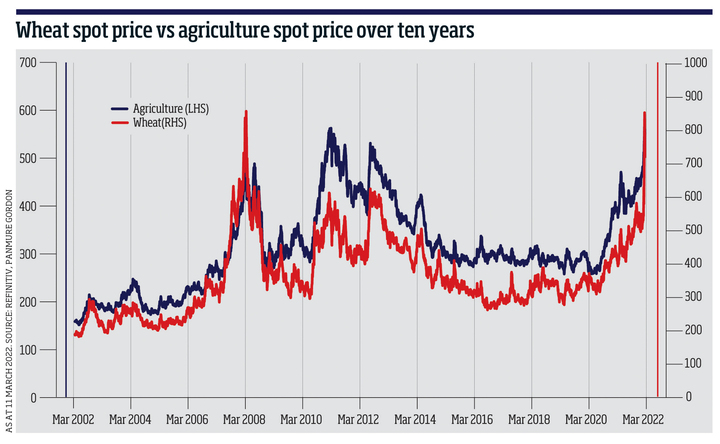

Much as I would like to claim foresight in this regard, the true cause has been, of course, the escalation of tensions between Russia and Ukraine into a full-blown invasion of Ukraine. This has clearly provided a supply shock to global food supplies. This, in particular, explains the additional upside experienced by wheat; Russia and Ukraine are the world's first and fifth largest wheat exporters respectively, accounting for a combined total of c25% of global wheat exports.

The Ukrainian supply is obviously facing sharp challenges, but Russian supply is facing logistical challenges to reach end markets too, with many major shipping companies refusing to operate in the Black Sea currently. These supply challenges saw wheat futures trade limit up on multiple consecutive days near the start of March.

Conversely, we have seen already that an expressed willingness of either side to pursue solutions that can bring about a cessation of hostilities sees wheat prices move sharply lower as these disruptions are assumed to dissipate. Unfortunately, the Ukrainian planting season is, essentially, now; even if we saw peace tomorrow, logistical challenges in labour and equipment availability, or of other essential material inputs (back to fertiliser, again) means we are unlikely to see a successful harvest. Wheat markets were tight coming into 2022; a supply deficit seems certain now.

Schroders: Ukraine crisis spells 'real risk' of global food shortages

Further pressures on supply seem likely later this year as fertiliser supplies constrict further. Russia and China have imposed export restrictions, while Belarussian suppliers have become unable to meet contracts for supply. Major producers of fertiliser such as Yara International, Nitrogenmuvek Zrt, and Borealis have been compelled to cut or halt output as a result of soaring natural gas prices.

Worse and worse, the Brazilian harvest has suffered under drought conditions (which have also made transportation, of crops produced, by barge more challenging, as river levels have fallen) and fertiliser shortages. Brazilian stocks have nonetheless continued to outperform in recent weeks, perhaps as domestic surpluses in energy and calories suddenly highlight the Brazilian economy as a potentially less fragile EM economy.

At this stage, further price increases, whether or not they materialise, are not even the problem; existing levels are a challenge.

Against this backdrop, we are seeing governments move; the Iraqi government, already facing street protests over food price rises, has instituted an emergency $100m fund to purchase wheat. Egypt's government has instituted bans on the export of multiple foodstuffs and urged changes to consumer habits amongst its citizens. Turkey's government insists they can offset with domestic production, but given they imported roughly half of their wheat last year (85% of which was from Russia or Ukraine), this looks like a fanciful assumption (and a dangerous one, when 51% of Turks were reportedly unable to afford food within the past 12 months).

Understandably, the Ukrainian government has now banned exports of food staples, joining a growing list of countries doing so. Globally, grain stockpiles have declined for the previous four years, and a fifth clearly seems on the cards.

IW Podcast: Transitioning from fossil fuels

For many emerging countries, the rise in food costs is likely to impact growth even if adequate supplies can be procured. The marginal ability to consume will be impacted, and countries that remain dependent on food imports will see consumption slow. Once again, the ‘Chinese consumer' thesis will be moved to the long-grass; despite heavy investment, a poor harvest has been forecast (not helped by topsoil degradation estimated at 40% of Chinese topsoil), and the Chinese economy remains dependent on food imports.

These problems are existential for large portions of the world's population. While disruptions to food supplies may well become notable in the West, the relatively superior buying power of the Western consumer should ensure we can outbid emerging countries for scarce supplies, for which we must be grateful. Yet the extra cost will surely be reflected in shopping baskets and fuel nascent wage inflation.

Globally, the fragility of food and energy supply chains which has been thrown into sharp relief by the current crisis seems certain to see more strategic reshoring or near-shoring of a plethora of industries. Wage inflationary feedback loops seem imminent; in such a scenario, we are reminded of the observations of the managers of Diverse Income trust (DIVI), that structural inflationary environments have historically led to UK outperformance. The investment world going forward could be a very different place from the last 30 years.

Callum Stokeld is an investment trust research analyst at Panmure Gordon