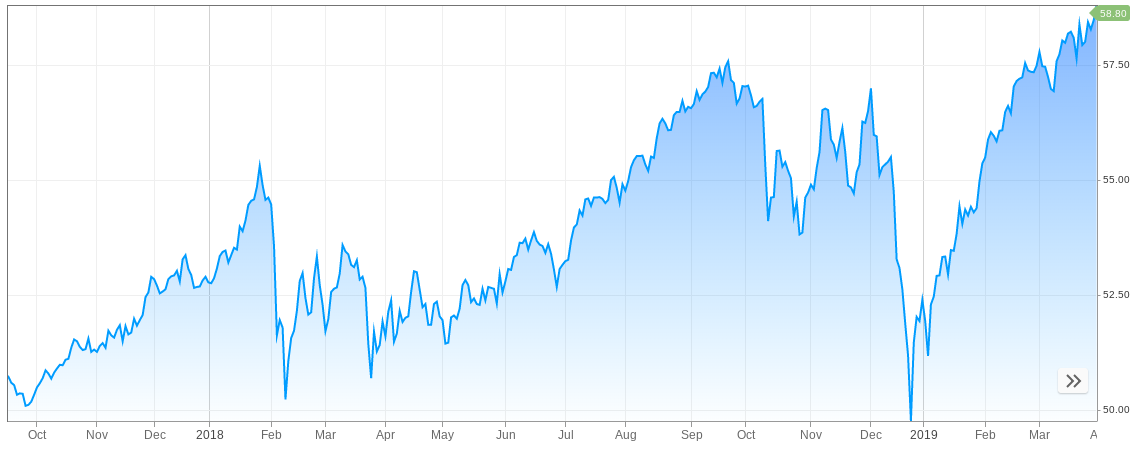

Hearing the superlatives applied to Wall Street's fast start — the S&P 500 up 13 percent, its best first quarter in 21 years — might leave the impression the bulls have routed the doubters decisively.

But it's closer to the truth to say that for two months, bulls rebounded from the devastating loss suffered at the end of 2018 by building up a nice 12 percent lead, and then for the past few weeks the defense has held off the bears to preserve it.

The first couple of months were a supercharged "January effect," in which the smallest, riskiest, most aggressive stocks sped higher as the fourth-quarter growth panic, fund liquidations and tax-loss selling abated. Then in March a turn toward more stable, less cyclical, yield-and-cash-flow plays stepped up and small caps sank, as bond yields rushed lower and global growth remained wobbly.

Those observers who defer strictly to the "message of the market" argue this defensive turn — combined with a furious bond rally and sudden outcry for a Federal Reserve rate cut — is a stark warning about heightened risk of recession and a downturn in corporate profits.

But what about the idea that inherently strong markets find a way to support themselves even when the data soften up and risk appetites waver? Maybe the fact that the S&P 500 in March underwent only a couple of fairly benign 2 to 3 percent pullbacks despite plenty of decent excuses to buckle further is the relevant feature of this market's character.

And perhaps the slight late-week lift in longer-term Treasury yields hints that the intense flight to bonds has tired itself out, releasing some pressure on financial stocks and leavening economic sentiment a bit?

Just to detail the market's defensive emphasis in recent weeks, among the industry groups with the highest proportion of stocks in a confirmed uptrend, defined as having a 50-day average price above its 200-day, are utilities, software, real estate and household products. Featured among the weakest: energy, autos, banks and transportation.